Catherine of Aragon, while exiled in Ampthill, Bedfordshire by her husband King Henry VIII, was said to have supported the lace makers there by burning all her lace, and commissioning new pieces. (This may be the origin of the lacemaker's holiday, Cattern's Day.) Subsequently, the court of Queen Elizabeth of England maintained close ties with the French court, and so French lace began to be seen and appreciated in England. Lace was used on her court gowns, and became fashionable.

Lacemaking centres in England

There are two distinct areas of England where lacemaking was a significant industry: Devon and part of the South Midlands/Eastern Counties. The first wave of lacemakers from the continent came in 1563-1568. They were Flemish Protestants who left the area around Mechelen when Philip II introduced the Inquisition to the Low Countries - Belgian lacemakers were encouraged to settle in Honiton in Devon. They continued to make pillow and other lace, as they had in their homeland, but "Honiton lace" never got the acclaim as that of Europe, although Queen Victoria was married in Honiton lace. Over time Buckinghamshire became established as the centre of English lacemaking.

The Eastern Counties

Lace was made in the Eastern Counties (Buckinghamshire, Bedfordshire, Northamptonshire), prior to 1563,

as it was and is still a flax growing area. A second wave of lacemakers, many from Lille, left in 1572 after

The Massacre of the Feast of Saint Bartholomew. Many hundreds came to Buckinghamshire (

Newport Pagnell and Olney),

Bedfordshire and Northampton, and from this time "Bucks point" lace developed : it is a combination of Mechelen

patterns on Lille ground, and often called "English Lille".

The Northampton Militia lists of 1777 states that there were 9-10,000 young women and boys employed in lacemaking

in and around Wellingborough and about 9,000 involved in the trade around Kettering. Nevertheless, it was the

counties of Buckinghamshire and Bedfordshire which were principally involved. For example the town of Newport Pagnell.

In good times, the trade paid 1/- to 1/3 (one shilling to one shilling and threepence ) a day; much better than

the wages of agricultural labourers.

‘…flourishes greatly, by means of the lace manufacture… There is scarcely a door to be seen, during Summer,

in most towns, but what is occupied by some industrious pale-faced lass; their sedentary trade forbidding the

rose to bloom in their sickly cheeks.’ Thomas Pennant – “The Journey From Chester to London 1779”

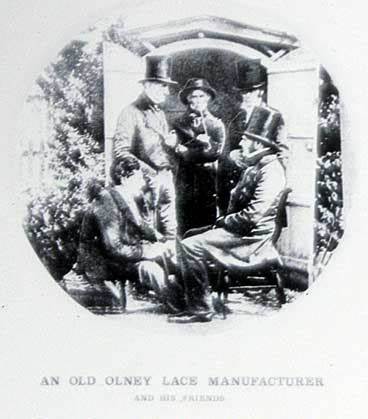

An Old Olney Lace Manufacturer and his Friends, about 1850

Olney in the Eighteenth Century had a population of around 2,000, and about 500 houses. As women often worked at

the pillows for ten to twelve hours a day, little time could be spared for domestic chores. A woman was employed

in the Town of Olney to do ordinary mending. Servants were hard to get; women could earn more at lace-making and

they had more independence. It was here that there was a Lace school for the Bucks Lace Industry.

Children as young as 5 years old were learning to make lace with a view to earning a 'living' for the rest of their

lives. Most of the lace made was Bucks Point. No lace maker ever made a complete piece of lace. They would learn one

pattern by heart to sell to the dealer. Each pattern would later be joined to complete the piece of lace to become

e.g. a flounce or shawl. William Cowper wrote in 1780 :-

Olney is a Populous place, inhabited chiefly by the half-starved and the ragged of the Earth.’

‘I am an Eye Witness of their poverty and do know that Hundreds of this little Town are upon the Point of Starving

and that the most unremitting Industry is but barely sufficient to keep them from it… there are nearly 1200

lacemakers in this Beggarly Town.’